Am I Your Pastor or Your Priest? It Depends Who’s Asking.

Clergy titles—preacher, pastor, minister, and priest—reflect distinct expectations: proclaiming, caring, organizing, and mediating the sacred. Each shapes how congregations understand ministry. My own draw toward the priestly role reveals how unfamiliar titles spark curiosity. What we call clergy forms both their identity and the community’s expectations.

It is not uncommon for clergy to be called different titles. These titles might reflect the tradition the speaker comes from, and that tradition might have a preferred role for a clergy person. The four most common titles I have been given in this way are:

Preacher

Pastor

Minister

Priest

Perhaps used interchangeably, these titles really are four different ways of being a clergy person.

The title preacher places unmistakable emphasis on the act of sermonizing. One of the clearest examples of the expectations woven into this title comes from a greeting I have received more than once: “Hey preacher, what’s the Word for today?” Whether I am standing in a pulpit or waiting in line at the pharmacy, the assumption is the same—the clergy person’s primary role is to preach.

I have walked into hospital rooms and been met with, “What are you doing here, preacher?” This is often said as a way for the patient to acknowledge that their condition may be more serious than they realized, or perhaps to apologize for inconveniencing the clergy person. But it also reveals another assumption: if someone understands the clergy person primarily as a preacher, then it feels strange to see that person in a hospital room. Hospital visits, after all, belong to the domain of the pastor, not the preacher.

The title pastor places the emphasis on care. I never took any courses in “preacher care,” but I took several in “pastoral care.” Because the pastoral identity carries a premium on caregiving, pastors often spend less time refining the art of preaching and more time developing their relational skills. During my internship, a pastor once said to me about preaching, “The congregation doesn’t care what you know until they know that you care.” One of the most iconic pastors I know is a man named Raul. Raul was not a strong preacher and was often late to events, yet he was given endless grace because everyone knew that Pastor Raul’s heart was consistently oriented toward serving others.

If the title pastor emphasizes relationships and individual care, the title minister tends to emphasize relationships and communal care. Ministers often give greater attention to structures, systems, and organizational dynamics because the scope of their responsibilities extends beyond what a single person can accomplish alone. There is likely a reason the words minister and administer share the same root. When I arrive at weddings I’m officiating, the coordinator usually asks, “Are you the minister?” The State recognizes clergy as administrators on its behalf. In addition, ministers are often expected to supervise others or manage systems in ways that preachers and pastors are not. In particular, the minister is presumed to have a stronger role in the temporal management of the church or congregation.

The title priest also emphasizes management, but it is aimed less at managing the temporal realm and more at stewarding the spiritual realm. The role of the priest is that of a mediator between earth and heaven. In many traditions, particularly within Catholicism, priests administer sacraments that are not understood in purely material terms. The sacraments are sacred, imbued with or transformed into something transcendent. In the priest’s hands, bread and wine become the body and blood; water becomes holy water; a simple bedside prayer becomes a rite for the dying; oil becomes Chrism. Of the four titles, priest is the one I have been called the least, yet people have asked me to fulfill priestly functions more times than I can count.

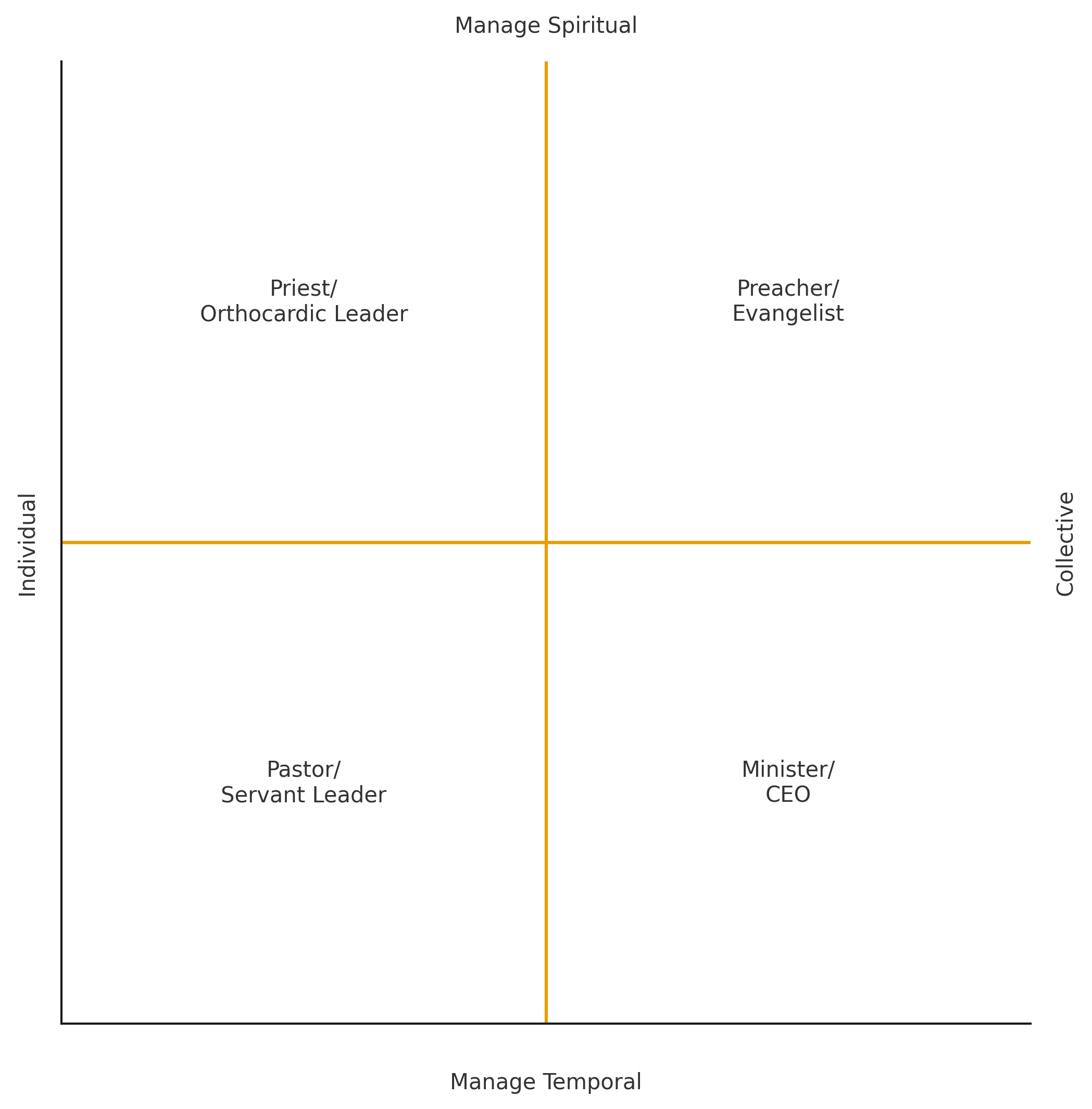

If we were to chart these four roles, we might picture a vertical axis distinguishing different forms of management and a horizontal axis highlighting whether the emphasis is on the individual or the collective. (Readers of Orthocardic Leadership – Pastoral Leadership Inspired by Desert Spirituality will also recognize how the four models—Orthocardic, Evangelist, Servant Leader, and CEO—fit naturally within this same matrix.)

In my local church, every clergy person is called “Pastor _________.” This is not because any of us requested the title—certainly not in my case as “Pastor Jason.” Rather, it reflects an embedded theological assumption within the congregation. In this community, the implicit expectation of clergy becomes explicit the moment someone names us.

Personally, I am drawn toward the role of the priest. Whenever I talk about Orthocardic Leadership in my tradition, the immediate response is usually, “I love the idea—but what does it look like?” My struggle to articulate it is partly a reflection of my own tradition’s limited experience with priests. Yet I have learned something surprising: the more I function in priestly ways, the more people express curiosity about ministry, religion, and Christianity itself.

What role or title do you implicitly associate with clergy? What we call clergy, and what clergy hope to be called, is never just a matter of preference. It is language that shapes both the clergy person and the congregation.

Clergy Isolation and Superchickens pt. 2

(For greater context, you may want to read part one in the previous post.)

In her TED Talk, Margaret Heffernan shares a study led by evolutionary biologist William Muir who was interested in productivity. Muir wanted to know if anything could be done to create more productive chickens, so he created an experiment. Heffernan explains,

"Chickens live in groups, so first of all, he (Muir) selected just an average flock, and he let it alone for six generations. But then he created a second group of the individually most productive chickens -- you could call them superchickens -- and he put them together in a superflock, and each generation, he selected only the most productive for breeding. After six generations had passed, what did he find? Well, the first group, the average group, was doing just fine. They were all plump and fully feathered and egg production had increased dramatically. What about the second group? Well, all but three were dead. They'd pecked the rest to death. The individually productive chickens had only achieved their success by suppressing the productivity of the rest.

We know that human beings are not chickens, but according to Heffernan, for the past half century, many organizations operate like the superchicken model. She says, "We've thought that success is achieved by picking the superstars, the brightest men, or occasionally women, in the room, and giving them all the resources and all the power. And the result has been just the same as in William Muir's experiment: aggression, dysfunction and waste."

Heffernan's talk goes on to share additional research done by MIT researchers who ran studies to determine what makes groups successful. Their research identified three characteristics. First, really successful teams showed "high degrees of social sensitivity" or what is sometimes called "empathy". Second, successful teams were mindful to give equal time for everyone to share so that no one or two voices could dominate the conversation. Finally, the more successful groups in these studies had a higher number of women in the group. It was unclear what it was about women specifically. Some say the since women typically score higher on empathy tests they brought more empathy to the group. Others say it may be that women add to diversity of view and groups benefit from diverse points of view. Regardless of the reason, what this study shows is that social connectedness matters in the success and productivity of groups. The more socially connected the greater chance of success. Or as Heffernan states it:

"What happens between people really counts, because in groups that are highly attuned and sensitive to each other, ideas can flow and grow. People don't get stuck. They don't waste energy down dead ends."

The reality is that the many UMC conferences are like other organizations, we build our leadership around the "superchicken" model. We direct resources and energies toward superchicken pastors and even superchicken local churches. The tragic irony is the more we elevate the superchickens, the more we unintentionally affirm the model that implies that one's "success is the result of suppressing the productivity of the rest."

For instance, local churches and even local pastors are not rewarded to collaborate. Each year local churches and pastors are asked about the ways that local church is bringing people to Christ and helping them mature in the Spirit of God. The local church/pastor are incentivized to speak about how they are doing that in unique ways. We reward individual creativity, we applaud individual effort and we ask the same individuals we think are successful to be the dominate teachers of our conference. There are explicit and implicit incentives to strive to be a superchicken church or superchicken pastor in ways that are perhaps leading us to peck ourselves to death. Conversely, there are too few incentives for local churches/pastors to connect, collaborate, and share. There is a fear of what will happen if the local church/pastor proves to not be creative or innovative enough on their own. The pastor may move or the church may be deemed as less successful or vital and receive less support. What makes superchickens successful is to out-think or out-do the other chickens with superior individual gifts and graces. If the superchicken were to share the secret ingredients of their "success-sauce", then superchickens become vulnerable to no longer being seen as a superchicken in a system that rewards superchickens!

Most leaders have thoughts on "how to fix" the problem. There are strategies and tactics to be sure that might be employed. However, the heart of the matter needs a better diagnosis. We need to seriously examine the emphasis on the "superchicken" model we have embraced.

Otherwise we will peck ourselves to death.

Clergy Isolation and Superchickens pt. 1

There is a strong biological incentive for us to avoid isolation. Like humans of today, early humans were dependent upon one another for survival. If a person was deemed by the tribe to be unclean, unfit, sick or inferior in any way, that person was marginalized from the group. Perhaps that person was excluded from the group. Left alone, without the support of the tribe, that person will struggle in life and perhaps even die. From these early beginnings, humans have figured out that there is a risk to do anything that might lead to exclusion from the tribe. This is part of the reason we do not do so well with criticism - if someone criticizes us then we run the risk of being excluded or pushed out.

Perhaps one of the more common feelings among clergy is that of isolation. I have heard from many clergy who feel isolated and they say they don't have a close friend they can confide in. Clergy often don't have the time to invest in relationships beyond the walls of the church. Additionally, the relationships that clergy do foster are often asymmetric, in that the clergy person cannot let down every wall and be completely vulnerable. Finally, the demands of the clergy role have gotten to the point that are so stressful that clergy are at higher risks for depression and anxiety.

What we face here is a feedback loop of destruction. Humans have a fear of being isolated, so we work harder to prove ourselves as worthy of the group. More work leads to less self-care and greater feelings of isolation.

This is compounded in the area that I serve because our area's focus is on "energizing and equipping local churches". It seems that one of the unintended consequences of this goal is there is less energy given to clergy health. When we choose to focus on energizing and equipping local churches we make decisions that, over time, exacerbate the feelings of isolation among clergy. Perhaps an example might be helpful.

In an effort to equip local churches with more resources, efforts are made to save money on a conference level. One money-saving action taken was cutting the number of districts. This resulted in lower apportionments, but fewer District Superintendents (DS) to support clergy. This puts more demands on a DS. More demands means less time to engage clergy in regular clergy meetings. These meetings between a DS and clergy are a place where clergy are expected to attend and support one another. With less clergy meetings, most clergy do not see any other clergy but a few times a year. The understood expectation is that with less clergy meetings, clergy are freed up to be at the local church, ensuring the "vitality" of their church. Clergy wanting to prove they are good enough to stay at their local church work harder to prove they belong there. And we quickly find ourselves trapped in the feedback loop mentioned above.

The more we as a conference focus on the local church, the more clergy are expected to take care of themselves - by themselves. Whereas the clergy connection was once fostered by the district it now is the sole responsibility of the individual clergy. There was an attempt to create a loose connection of clergy through "cluster groups." For a number of reasons, this was unsuccessful as envisioned. At one time, Texas Methodist Foundation created clergy groups, but even fewer new groups have been formed in the past several years. Without an incentive that is stronger than the current push to focus on the local church, the model clergy-driven group formation will be limited. Group formation will be reserved for those who have a support staff to stay at the local church while the clergy attends these gatherings.

Perhaps the most tragic of ironies is that not focusing on clergy health, achieving the goal of energizing and equipping local churches is in grave danger. Not just because we will see more and more clergy drop out of the ministry because of stress, anxiety, and feelings of isolation, but because the local church itself is very limited to do anything that creates lasting change in the world. Most churches do not have resources to make a measurable difference in their community because the problems are complex and a local church does not have ability to scale up to meet these problems head on. Local churches are doing their best to do vital ministry, but are coming to realize that band-aids do not do much in a world that is so deeply wounded. Churches are constantly on a treadmill of addressing problems for years without any progress. How many churches have a food distribution ministry but Texas still has higher than the national average of people who are food insecure? It is not that these ministries are bad, it is that they are too small and often cannot be scaled to the size they need to be to treat the problem of hunger.

In a effort to streamline the leadership of the conference, we have created districts that are connected in name only, supervisors (DS) who do not feel empowered to bring clergy together out of fear of being seen as one who creates "another thing" for clergy to do, pastors who feel more and more isolated in a system that claims connection as its cornerstone, and churches with ministries only able to address the symptoms of a deep social sickness.

How do we move out of this feeling of disconnected churches, overextended District Superintendency, isolated clergy and "symptom ministries"?

Might I suggest we look to chickens.

If you have read to this point then I thank you and will let you know that the next post will unpack a little more about how chickens can help with clergy isolation.

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.