Am I Your Pastor or Your Priest? It Depends Who’s Asking.

Clergy titles—preacher, pastor, minister, and priest—reflect distinct expectations: proclaiming, caring, organizing, and mediating the sacred. Each shapes how congregations understand ministry. My own draw toward the priestly role reveals how unfamiliar titles spark curiosity. What we call clergy forms both their identity and the community’s expectations.

It is not uncommon for clergy to be called different titles. These titles might reflect the tradition the speaker comes from, and that tradition might have a preferred role for a clergy person. The four most common titles I have been given in this way are:

Preacher

Pastor

Minister

Priest

Perhaps used interchangeably, these titles really are four different ways of being a clergy person.

The title preacher places unmistakable emphasis on the act of sermonizing. One of the clearest examples of the expectations woven into this title comes from a greeting I have received more than once: “Hey preacher, what’s the Word for today?” Whether I am standing in a pulpit or waiting in line at the pharmacy, the assumption is the same—the clergy person’s primary role is to preach.

I have walked into hospital rooms and been met with, “What are you doing here, preacher?” This is often said as a way for the patient to acknowledge that their condition may be more serious than they realized, or perhaps to apologize for inconveniencing the clergy person. But it also reveals another assumption: if someone understands the clergy person primarily as a preacher, then it feels strange to see that person in a hospital room. Hospital visits, after all, belong to the domain of the pastor, not the preacher.

The title pastor places the emphasis on care. I never took any courses in “preacher care,” but I took several in “pastoral care.” Because the pastoral identity carries a premium on caregiving, pastors often spend less time refining the art of preaching and more time developing their relational skills. During my internship, a pastor once said to me about preaching, “The congregation doesn’t care what you know until they know that you care.” One of the most iconic pastors I know is a man named Raul. Raul was not a strong preacher and was often late to events, yet he was given endless grace because everyone knew that Pastor Raul’s heart was consistently oriented toward serving others.

If the title pastor emphasizes relationships and individual care, the title minister tends to emphasize relationships and communal care. Ministers often give greater attention to structures, systems, and organizational dynamics because the scope of their responsibilities extends beyond what a single person can accomplish alone. There is likely a reason the words minister and administer share the same root. When I arrive at weddings I’m officiating, the coordinator usually asks, “Are you the minister?” The State recognizes clergy as administrators on its behalf. In addition, ministers are often expected to supervise others or manage systems in ways that preachers and pastors are not. In particular, the minister is presumed to have a stronger role in the temporal management of the church or congregation.

The title priest also emphasizes management, but it is aimed less at managing the temporal realm and more at stewarding the spiritual realm. The role of the priest is that of a mediator between earth and heaven. In many traditions, particularly within Catholicism, priests administer sacraments that are not understood in purely material terms. The sacraments are sacred, imbued with or transformed into something transcendent. In the priest’s hands, bread and wine become the body and blood; water becomes holy water; a simple bedside prayer becomes a rite for the dying; oil becomes Chrism. Of the four titles, priest is the one I have been called the least, yet people have asked me to fulfill priestly functions more times than I can count.

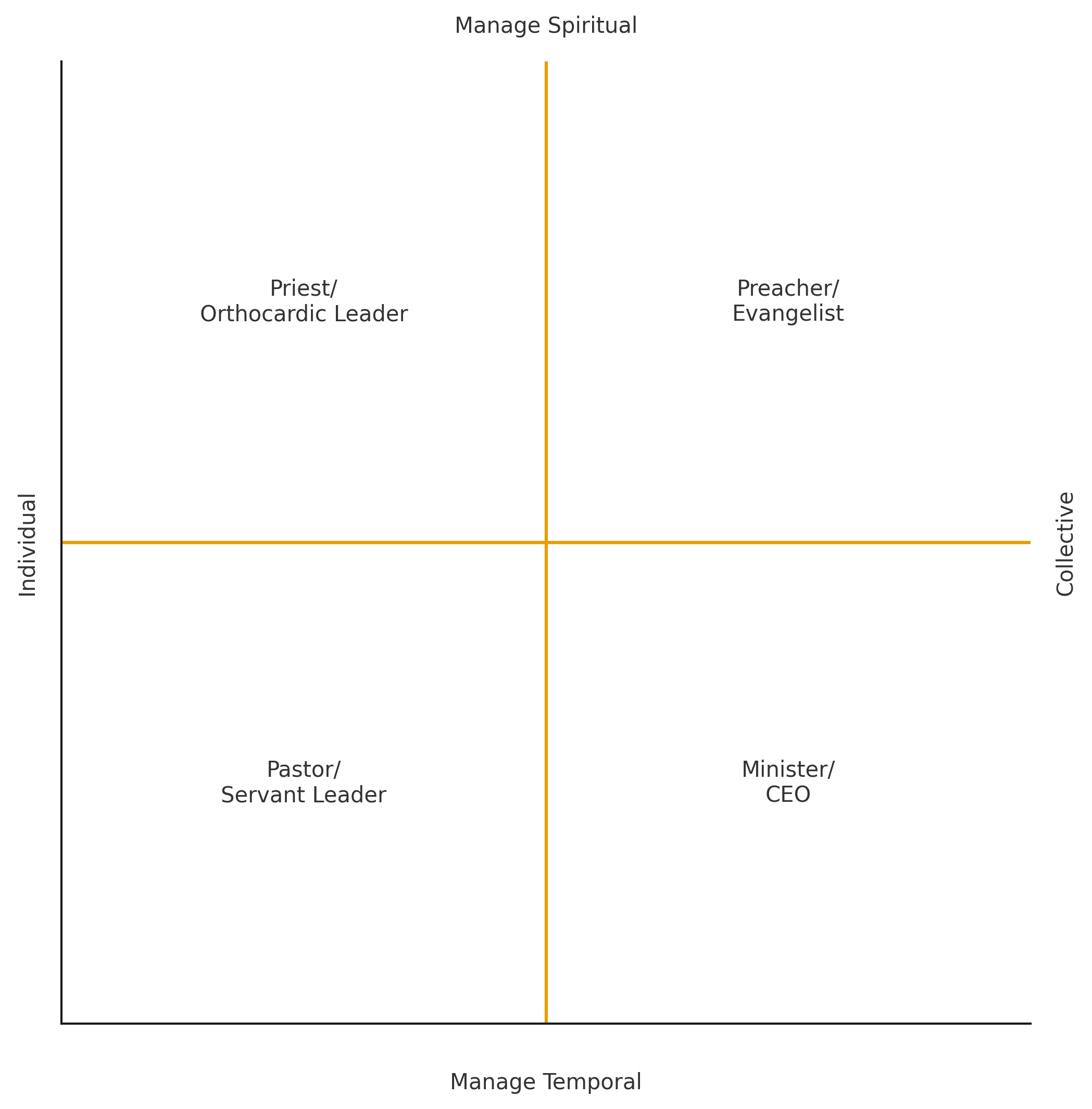

If we were to chart these four roles, we might picture a vertical axis distinguishing different forms of management and a horizontal axis highlighting whether the emphasis is on the individual or the collective. (Readers of Orthocardic Leadership – Pastoral Leadership Inspired by Desert Spirituality will also recognize how the four models—Orthocardic, Evangelist, Servant Leader, and CEO—fit naturally within this same matrix.)

In my local church, every clergy person is called “Pastor _________.” This is not because any of us requested the title—certainly not in my case as “Pastor Jason.” Rather, it reflects an embedded theological assumption within the congregation. In this community, the implicit expectation of clergy becomes explicit the moment someone names us.

Personally, I am drawn toward the role of the priest. Whenever I talk about Orthocardic Leadership in my tradition, the immediate response is usually, “I love the idea—but what does it look like?” My struggle to articulate it is partly a reflection of my own tradition’s limited experience with priests. Yet I have learned something surprising: the more I function in priestly ways, the more people express curiosity about ministry, religion, and Christianity itself.

What role or title do you implicitly associate with clergy? What we call clergy, and what clergy hope to be called, is never just a matter of preference. It is language that shapes both the clergy person and the congregation.

What is the training of a Christian?

When I was younger I played soccer. I was above average, but no Messi. Becoming a soccer player required training: first I had to learn to dribble, then pass, then trap the ball, then pass with accuracy, then shoot, then learn to play with others, read the field, see the space, formations, timing, etc. This training took years to get decent at. Countless hours a week with coaches and others in practice and games.

And that was just something as simple as soccer.

Becoming a Christian requires more training than we are want to believe. (We forget that the disciple were with Jesus all the time for three years and they still did not get it.)

What is the training of a Christian?

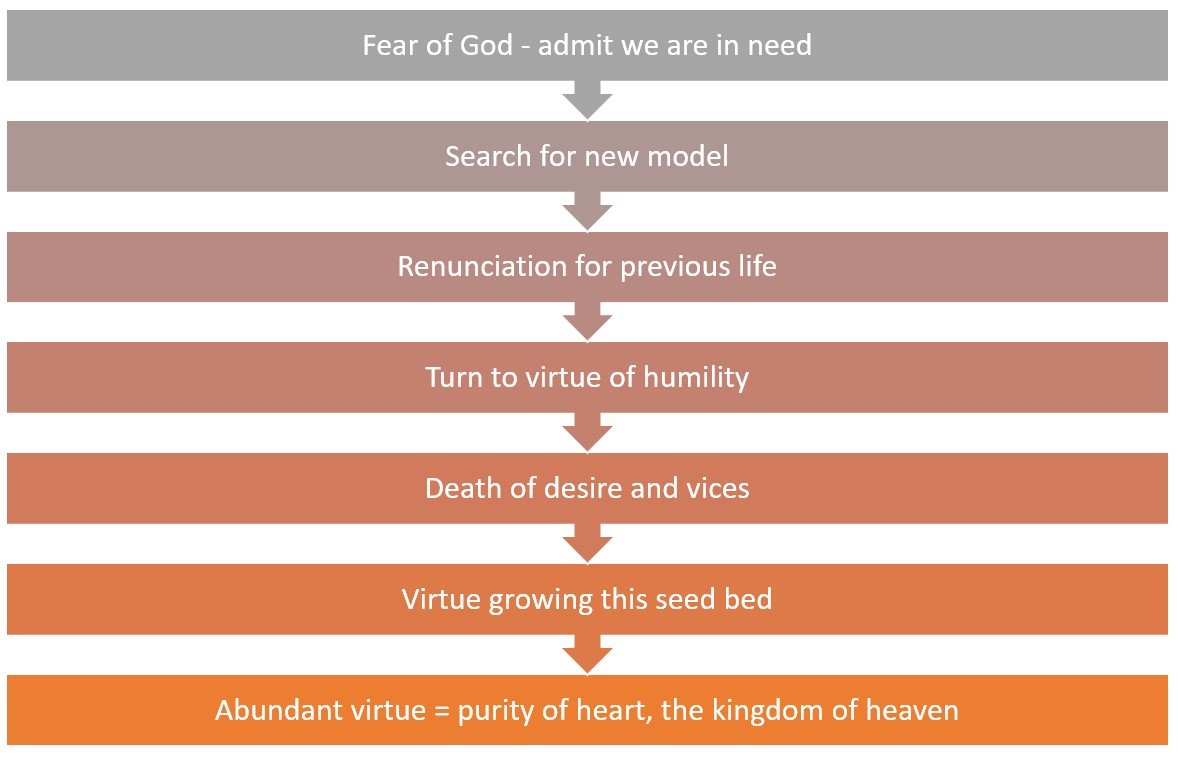

John Cassian suggests that there is a training process that one engages to develop into a Christian. In the the fourth book of The Institutes he describes this process:

First it begins with the fear of the Lord that is the beginning of wisdom (Proverbs 9:10). What this means is that one must come first to see they are in need. To put it another way, the fear of the Lord means that we admit that the current models of our lives are leading us poorly and we need a new model to guide our lives.

We cannot adopt a new model while holding onto our original model. We cannot worship two gods (Matthew 6:24). This is why we must renounce our first models/gods. We must repent. This repentance is total. It is a repentance of all the objects, values, teachings and ways of the original model. It is impossible to learn a new life while holding onto the “way we used to do it”. It would be like learning to play basketball while still using a soccer players mindset, skills, tools and techniques. It does not work that way.

When we renounce our previous ways/models we are like a beginner. And there is nothing more humbling than being a beginner at anything. Which may be why we do not repent or renounce totally. We hold on to some things so we are not tossed into beginner status. However, when we are able to renounce/repent our previous life, dreams and desires fall away and die.

As Jesus said that a seed must fall to the ground and die in order to grow (John 12:24). When our old ways and models have died, then we are able to receive what the new model has for us. This new model, Christ, trains us in virtues that produce the fruits of the spirit - love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control.

The person who produces such fruits of the spirit has an altogether new heart, what we might call the purity of heart. It is, as Jesus says, the pure in heart that see God (Matthew 5:8).

This training takes a lifetime and it is not easy. It breaks us down into being a new creation (2 Corinthians 5:17). In this training, you may see that this does not begin by training people to just be better humans. It does not start with behavior modification to be more loving or kind or forgiving. It understands that we are unable to be loving, kind and forgiving as long as we living out of a sense of self and without seeing that we are in need. Without seeing that we are in fact in need we will reserve our love, mercy and forgiveness for only those who “deserve” or “earn” or who are “worthy”. Until we repent and renounce this way of living, we will not see God.

We will just see ourselves as god.

Am I Growing In My Faith?

How do we know if we are progressing in our faith? How do we know if we are digressing in our faith? How do we know if we are stagnate in our faith? It is commonly taught that it is the fruit of our faith that matters and so we should just look to the fruit of our faith and then we know if we are progressing, digressing or stagnating. This way of thinking might overlook that a child can be full of kindness but that does not mean they have a deep faith that will help in time of need. Or even the most patient person might still desire to be correct all the time. So they are patient and self-righteous.

And so how do we know if we are progressing in our faith? One way to think about it is where we see God. More specifically we might think of the spiritual life as moving from:

Seeing God where we expect

Seeing God everywhere

Unable to see God

Seeing God where we do not expect God to be

What follows is a brief unpacking of each of these different movements, or different faiths.

There first is being able to see God where we expect to see God. This is the “reassurance faith”. We move through our world and we expect to see God in nature and so we look out and we see God in a sunset or a blooming grove. We expect to see God in the good, true and beautiful. We associate God with these things and so when we see something good, true and beautiful, we expect that God is there. And we see God. And that reassurance is soothing. It allows us to return to the good, true and beautiful when we are stressed, anxious or crumbling to be reassured that God is where we expect to see God.

However, as we experience the broader world, we begin to think that maybe God is not just limited to the light and beautiful. We begin to think that maybe God is also located in the night and darkness of our souls. We see God not just where we expect to see God but we begin to see God everywhere. Yes, God can be seen in a lovely daybreak but also in the heartbreak. God is present everywhere and there is no place where we can go that God would not lead us. This is the “purity faith”. Some stop at this level and think that if God is everywhere then I don’t need to participate in a worshiping community to see God because God is not just where I expect (such as in corporate worship) but God is also with me when I read a book with coffee early in the morning. Seeing God everywhere is a great step and it feels like we are going deeper, but in practice we begin to believe that God is where I am and I am where God is. While an important movement, remaining at this stage makes our sense of God rather small.

It makes sense why we might want to stay at “purity faith” because it gives us permission to retain our innocence without having to address the difficult question, such as: Can God be in the tragic? Where is God in this terrible things? Surely God is not in the evil thing, right? The inner conflict we have to see God everywhere but not being able to see God everywhere creates cognitive dissonance. Some of us resolve this dissonance by tossing our hands up and go back to “purity faith”. Others embrace a “material faith”. This is when we are not able to see God, and since we cannot see God, maybe God does not exist. To be clear, “material faith” is not atheism. It is not a rejection of a God, rather it is just a redirecting of what one has faith in. Maybe one begins to have faith in one self or in what is measurable or testable. Even the most ardent “atheist” has material faith, it is faith that rejects the intangible or the non-material.

The “deepest” movement that I have experienced is the movement into “contradiction faith”. This is most commonly experienced when we see God where we don’t expect God to be. When we are able to see God in the "other” or even the “enemy”. When we are able to see God in places where we do not expect God to dwell or be. When we are scandalized by the idea that God is present in the hells and demons of this world. Many of the most ardent faithful Contradiction faith looks silly, wishy washy, inconsistent and even to some, evil. At it’s core, contradiction faith is being able to be surprised by God’s presence. It is unpredictable and vibrant. It is a freedom from having to solve or overlook inconsistencies in our faith. It is being able to see that contradiction is not to be avoided but to be embraced, because the very world is full of contradiction.

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.