Giving: A Brief Taxonomy

For a bit of time now I have been wrestling with the differences between a gift, a tithe, an offering and a sacrifice. I identify more as a practical theologian than a philosopher and so please forgive if this small taxonomy is reductionist or too simple by academic standards. The goal is to examine the differences in these four ways of giving so it might nudge us to examine our giving - especially in the “season of giving”.

To state an easy point: There are three components of giving - giver, object, and receiver.

To state a slightly more complex point: There are two elements in giving, 1) a desire to control a response and 2) control of the object.

If we put the first element on a matrix it might look like this:

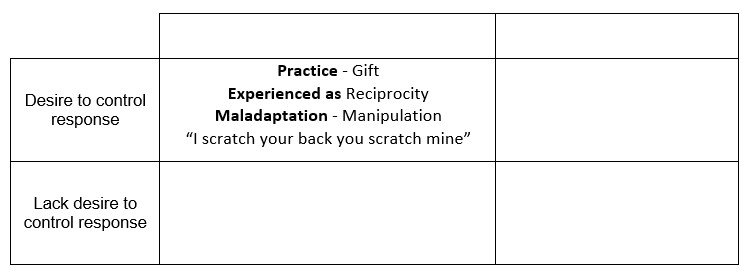

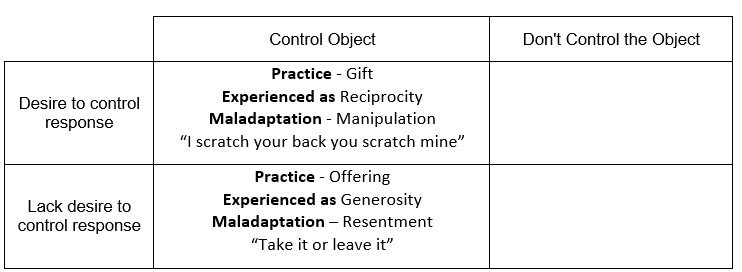

Now, if the giver desires to control the receiver’s response, this type of giving might be understood in the saying “I’ll scratch your back and you scratch mine.” The giver gives with the hope to control the receiver’s actions, such as with words of appreciation or a future object from the receiver. But the goal of the giver is to give an object with the hope to control the receiver’s response. This sort of giving is experienced by the giver and receiver as reciprocity but we identify this sort of giving as “gifting”. We give gifts in order to foster relationships and control the receiver to “give back” in some way. In every act of giving, there is the possibility of a maladaptation and the act of giving is harmful. When the desire to control the response is so powerful that the giver gives to manipulate . Adding to our matrix we get this:

Of course the giver does not always desire to control the receiver’s response. For instance, when we give something with an invitation to “take it or leave it”. The giver is not offended if the object is taken or if the object is rejected. This freedom the receiver has to reject is not present in the above "“gift giving”. In fact, it is rude and potentially hurtful to reject gifts, which is captured in the caution to “not look a gift horse in the mouth.” Even the softer forms of rejecting a gift are up for discussion which we see play out in conversations regarding “re-gifting”. If the receiver were free to reject the gift then the practice of “re-gifting” would lack the social taboo. And so this second type of giving cannot be called “gifting” but is called “offering.” The giver offers the object without a desire to control the receiver’s response. That is why an offering is always experienced as generous, not because of the value of the object but because of what the object lacks. An offering lacks the desire to control that is present in gifting. Many times humans are taken aback by generosity and/or are made uncomfortable by it and the receiver will want to give something in return. Ironically the receiver can cheapen the generous act by reciprocating the gift (which may be why many people give anonymously to different causes). Perhaps the more insidious maladaptation that can develop in an offering is resentment. For instance, when the giver makes multiple offers over time and no one “takes up the offer” the giver might grow resentful towards others and begin to feel like what they have to offer is worthless. One could say that when we grow resentful in our offering, we are no longer giving an offering but moving into gifting. But for the purposes of simplicity, here is offering represented in the matrix:

The first element of giving considers if the giver desires to control the receiver’s response.

The second element of giving considers if the giver has control over selection of the object.

And so our matrix takes an additional form:

In both gifting and offering the giver is choosing what the object is. From a birthday present (gift) to an offer of services (offering) the giver controls the type, amount and frequency of the giving action. However, these are not the only ways to give. There are other ways to give in which the giver does not have much say or control over the object that is to be given. For instance, in the Bible there are a number of laws which dictate the specific object that is to be given. Mary and Joseph were to give to turtledoves as an offering for the consecration of the son, Jesus. In this act of giving, the object was not something that Mary and Joseph chose, it was a directive. Some may call this type of giving as a tax, but for our purposes I am choosing the religious term of “tithe”. The tithe is not limited to the type of object but the specific amount, 10% of the whole. If you are a farmer or a banker, giving a tithe means you are giving a set amount and that amount is prescribed from a “big other”. This “big other” could be god or a government or a parent who died years ago, but giving out of obligation or duty (as the Australian philosopher Peter Singer) is when the giver does not control the object but desires to control the response of the “big other”. It may be to fit in with society, or be seen as faithful, be marked as a law-abiding citizen, or be seen as one who gives, or trying to please God or a parent. Like other forms of giving, this third form of giving can be maladaptive when it is experienced as guilt for failing to give to the standard of the “big other”. Some religious folk often wonder if they are giving enough and many citizens pay their taxes in full so they do not go to bed at night with the guilt of “cheating” on their taxes.

The fourth type of giving is the giving in which the giver not only lacks a desire to control the response but also does not control the object that is being given. This type of giving is perhaps the most radical and it is the sacrifice. If one controls what is being given then there is a comfort in giving. For example, being a care taker of an animal. The giver cannot control all that would be asked of the giver. The animal may get out of the yard while you are at work and you have to go home to fetch the dog. You as the giver did not control when you would give this object of time to the dog, it was demanded of you by a “big other”. The sacrifice not only lacks control of the object given, but the giver also lacks a desire to control the outcome. For instance, no matter how much time a parent gives to a child, the parent cannot control how the child "turns out”. While not limited to the solider, the parent, the guardian, the care taker, the teacher, these are all are arenas where sacrifice is more common.

At the core of Christianity is sacrifice. The first is when God become human. God gave up divinity for humanity and God gave up control how people responded. Another sacrifice of God is on the cross. Here God did not control what was given, that was demanded by Rome. Additionally, God in Christ did not control how people responded at the point of his death and resurrection. At the very core of Christianity is sacrifice and sacrifice has two expressions. The first is what is called “kenosis” which is giving of oneself when it is demanded of you. The maladaptive expression of sacrifice is violence.

There is not a “good” of “bad” type of giving. Each has its place and purpose. What I hope to offer in this short reflection is that what we often call sacrificial giving is more aligned with the “Tithe”. Perhaps those who are great at giving “gifts” are not very good at giving “Offerings”. Maybe our giving is limited in scope and one way we may discover more about ourselves (and God for that matter) is to explore other ways of giving.

Communion is Disgusting on Purpose

I no longer see a barber or hairstylist. I don’t think that I am too good to see a professional, but even a professional pianist cannot do much with piano that only has ten keys.

However, when I used to have a full keyboard, one of my favorite questions to ask the barber was, “If you see hair in your meal at a restaurant, would you send it back?” I have not done a scientific study of the number of people I asked and their responses, but the majority of barbers I asked said they would not send their food back. The reason? They shared that it is was more likely that they were the ones who had loose hair on them that fell into the meal. The vast majority of barbers said they would just pull the hair out and keep on with their meal.

Like it is no big deal.

Doctors talk about blood stuff with family members over dinner while everyone else gets queasy. Vets talk about lancing wounds on an animal, ranchers speak of pulling calves as they are birthed, and plumbers talk about the stopped up pipes they had to endure.

Like it is no big deal.

For so many of us, these topics trigger a sense of disgust, but these folk have crossed some disgust bridge. These topics are no longer disgusting. They are not a big deal.

Disgust is an “expulsive” response. It is that feeling of pushing things away or expelling them from your body. Humans are disgusted by so many things and sometimes, unfortunately, we feel disgust toward our fellow sisters and brothers. We push away the smelly, dirty, and unkept. We expel those who we think are unclean in some way. It can manifest in ways like pushing those who are sick away from us so we don’t get sick to pushing those who have a different culture away from us out of fear they will freeload. Disgust is a powerful influencer of our behavior and left unchecked it harms.

Christians have a sacrament called communion or the eucharist or the Lord’s supper. In a sacrament in which we say that the bread is the body of Christ and the juice/wine is the blood of Christ. Taken at face value, it makes sense why early Christians were accused of being cannibals.

This sacrament is mysterious and has a lot going on, but at a fundamental level communion addresses our disgust. We are associating bread with flesh and wine with blood. We make food associations all of the time. Many foods we don’t eat, not because they do not taste good but because of the texture (I struggle with eating the delicious lychee fruit).

The associations made at communion are intentional to aid and push us to encounter our disgust. If we can overcome the disgust of eating and drinking while thinking of flesh and blood then, surely we can overcome the disgust we feel toward our neighbor. Christians take communion as much as possible, in part, to practice confronting our own disgust toward each other. The more we confront the disgust we feel the more comfortable we are with these matters and the less expulsion we feel we need to do.

In this way, Christians are like the barber who is no longer disgusted with unknown hair in their food. There is no longer a need to push the food (or people) away, but rather bring it in close. Communion helps us invert our disgust and see that Christ does not call us to expel one another. That purity is an abstraction. That holding to what is clean only creates division among the body.

All of which to say that when a church leaders push for a “better” or “more faithful” or "traditional” or “prophetic” expression of the church, this is a nicer way of speaking about disgust. Disgust is always an expulsive response. We can expel others or we can expel ourselves. We can spit the food out (expel others) or we can avoid the restaurant entirely (expel ourselves). We can kick people out of the church who are unfaithful or we can remove ourselves from a church we “know” is unfaithful. Until we address the disgust we Christians have yet to overcome we will find that the denominational splitting will never end. Until we have a church of one.

Communion is disgusting on purpose.

"You are a sinner but you are saved" undercuts the Gospel

The faith “formula” many of us have heard goes something like this:

Everyone is a sinner. We all fall short and we need salvation.

The consequence of sin is death and so since we are sinners we all deserve to die.

The death of Jesus Christ paid the price of the world’s sin…

And so, anyone who confesses Jesus Christ and places their trust in him is saved from eternal death because Jesus died in your place.

It is a tidy formula and there is little here that Christians would call into question. Some quibble about what the death of Jesus really accomplishes, and still others argue about the different atonement theories. Some progressives insert a step before step one above by saying something like, ‘before there was original sin, there was original blessing.”

In the end, most Christians that I encounter (of all sorts of leanings) share the Christian story as moving from sin to salvation, from sinner to justified. You are a sinner but you are saved. The problem is that this story undercuts the power of the Gospel because of the “but'“.

Ask any human you know about what it is like to hear a “but” in a conversation and you will hear a common refrain, “nothing someone says before the word but really counts.” It is why managers and parents are taught to avoid the “compliment sandwich” - giving someone a complement then provide a point of critique. People do not hear the complement and only hear the critique. It does not matter what was said before the ‘but’ because it does not matter in the mind.

And so, back to the common salvation formula: You are a sinner but you are saved. We don’t hear that we are sinners and only hear that we are saved. While this may be good news to our egos, it is not the Good News of Jesus Christ. The Good News of Jesus Christ is more akin to what Luther suggested, “Simul Justus et peccator” - Justified and Sinner.

In this just as simple formula, the but is removed and the two positions are made equal. You and I are justified AND sinners. Secondly, notice that in the common telling, the humans are the first actors - humanity sinned. Being justified and sinner proclaims that it is God who is the first actor. Even before you were aware of it, before you acted, God acts. In the Methodist tradition we say this is prevenient grace - grace that goes before you are aware of it.

But the most potent aspect of being justified and sinner is that it is not good news to the ego but it is Good News in Jesus Christ. This way of seeing God’s grace means that you are justified, you are forgiven, you are made right by God AND still you are a sinner. Name any other relationship in the world like that. Betcha can’t. Humans build our relationships on the premise that we expect each other to become less and less of a sinner, problem, immature jerk. And that the future of the relationship is at stake if you do not “get better”.

The Good News, the Gospel News of Jesus Christ, says that God’s work justifies, redeems and forgives - no matter what! And when we come to see there is nothing that can separate us from the love of God (not even sin), then we interact with the world and with God differently. We no longer look to please out of fear, rather we are pleased to look through fear.

You are a sinner but you are saved is a very human formulation. Any parent will say this to their child. It pleases the ego to hear this.

You are justified and a sinner is revolutionary and only the imagination of the divine could consider this as a way to the death of the ego and the resurrection of a new creation.

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.