Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The Real Problem of Thanksgiving Conversation

There will be countless articles and hot takes given on how to “survive” Thanksgiving table conversation. We know the unwritten but often expressed rules of Thanksgiving conversation:

No Politics

No Religion

No past hurts

Keep it light and happy

If you cannot do these things, eat another slice of pie

These rules are fine and I am sure they serve a purpose in many households. The real problem of Thanksgiving conversation is that there are many rules for talking but none for listening.

There are no rules, spoken or unspoken, about how we are to listen at Thanksgiving. No one to tell us that one of the greatest acts of love we can do for another is to listen to them. If we give thanks for anyone in our lives, then the act of listening matters.

One rule for better listening at Thanksgiving is what we might call the two hand rule. The two hand rule is simply this: When you hand someone something at Thanksgiving, use two hands.

When we hand someone using only one hand we do not have to look at that person. We can still engage in our own world and not even pay attention to the person we are handing things to. We can pass the potatoes while looking at the turkey coming down the row. The ways we hand things to people often mirrors how we listen to them.

The two hand rule results in physically turning your body to face and see the other person you are handing things to. You have to look at them. You have to see them. You have to face them. It is much harder to say things that are hurtful to someone you are looking directly in the face. If there has to be rules Thanksgiving conversation, maybe we could offer up this list:

Face one another

Share a meal

Use two hands

Keep it meaning and memorable

If you cannot do these things, eat another slice of pie

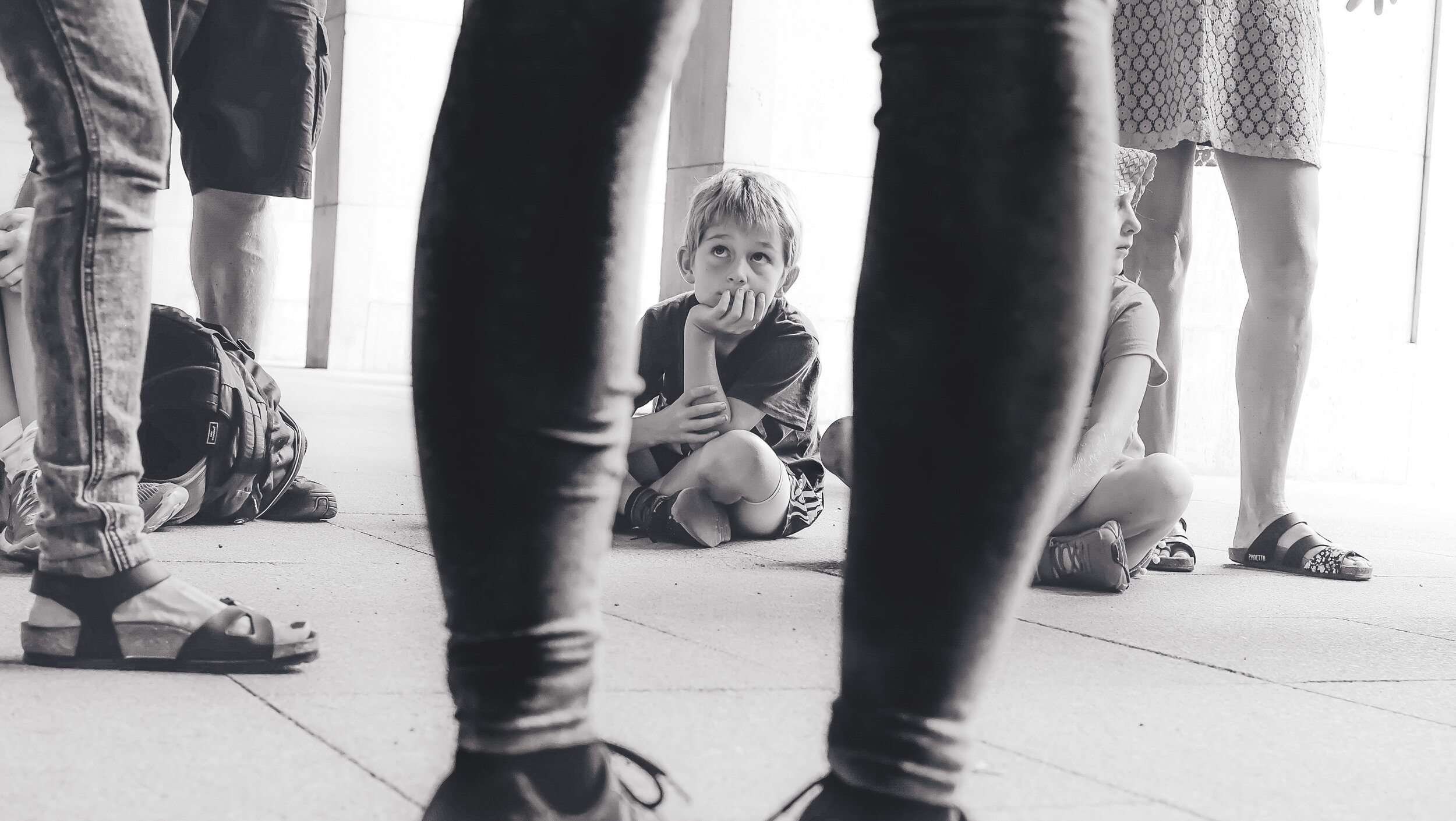

Learning From Observation Over Conversation

The Lives of the Desert Fathers by Norman Russell opens with this little story expressing why people would seek out holy men and women in the deserts of Egypt in order to learn from them:

We have come from Jerusalem for the good of our souls, so that what we have heard with our ears we may perceive with our eyes - for the ears are naturally less reliable than the eyes - and because very often forgetfulness follows what we hear, whereas the memory of what we have seen is not easily erased but remains imprinted on our minds like a picture.

Russell adds, that these pilgrims desired to learn from conversation with these desert sages, but more so pilgrims desired to learn from observation.

It is not deeply profound to be reminded that actions speak louder than words. It is not new that we best learn from doing rather than listening. And yet we continue in the Church to lean very heavily on the spoken word to teach others.

Preachers are important, but not in the ways that preachers think we are. Preachers are important not just for the words they say (the conversation) but through the lives we live. People listen to preachers who live lives that are compelling, interesting, different and authentic. For all the sermon classes and preaching tips I have taken, I have yet to be in such a training that elevates the life of the preacher over the words of the preacher.

That is, we preachers still elevate conversation over observation.

The truth is that conversation is easier than observation. Teaching by conversation does not require one to be open to the Spirit of resurrection. Teaching by observation does.

So take a look at the Church we serve. Many people are learning from us not by what we say in sermons or doctrine, but by observing our lives. Maybe God was onto something when it was proclaimed that God desires mercy and not sacrifice (Hosea 6:6, also echoed by Jesus in Matthew a few times). God desires mercy and compassion over the dogmatic and orthodox sacrifices that our religion demands.

Oddly enough, one does not have to know anything about religious practices to be merciful but you need to know a lot of religion to practice the proper sacrifices.

Learning through conversation is good. Observation is better.

The Evil of Our Public Lives

When I was younger I was told that if I was not willing to do something in public, then I ought not do it in private. The concern was that what we did in private was potentially more evil than what we would do in public. There may some truth to that for most of us - especially in our teenage years when we might violate social norms or rules in private (Kevin Bacon might owe his career to such a truth).

While the concern of evil lurking in the private was emphasized, the inverse was all but ignored. That is, sometimes we would do things in public that we would never do in private. The concern that what we do in public was potentially more evil than what we would do in private was never really considered.

However, the reality is the more we ignore the latter the more we are prone to participate in evil in the world.

The evil of the public life memorialized in the coliseum

Most people would not privately whip themselves into a frenzy and loot, harass or kill. Yet groups do this all the time. Most people would never breathe threats of violence toward another, but then we get online and that is often what we do.

If the story of Jesus teaches us anything it is that our public lives can be more evil than our private lives. We can kill the very Christ of the world in public displays. We can loot the very heart of God in public elections. We can be like Saul and become the mob of violence and retribution in public.

Maybe we need to take some of our concern that our private lives are evil and examine our public ones.