THE Scientific Method is a Misunderstanding

Elementary school science class taught me a basis outline of “the scientific method”. I do not recall the specifics but what has stuck with me is the overall flow of: hypothesis, test, measure, and conclusion. Recently I was informed that “the scientific method” is incorrect. Not the method, but the idea that there is THE (or just one) scientific method. Different sciences have different methods.

For instance physics has a method that works for Newtonian physics but quantum physics is more theoretical than material. Biologist have the benefit of knowing the results of their hypothesis much quicker than geologists who have to have a different method while waiting eons for rocks to move. The sciences have methods that make sense in their field but might not make any sense in another field.

Of course, these different methods are neither better nor worse than one another. While these methods are different in their specifics, in a general sense these different methods are unified in their efforts to better understand the mysteries of the world.

These different methods also contribute to a humility among the most respected scientist. A zoologist does not over reach into the field of astronomy in order to correct or condemn. The zoologist knows there are limits to her field and her understanding and those same limits exist in the astronomist. Each field respects the methods of the other fields. There is no attempt to prove the superiority of one fields methods over another. Criticism comes from within the same field - chemists argue with chemists.

For as much as religion has to teach the sciences, I wonder if religion has something to learn from science.

Scripture is the Christian DNA

Christian historian Phyllis Tickle argues in her book "The Great Emergence" that every 500 years there is a great "rummage sale" of culture. Similar to the shows on television that help people organize their life, culture sorts things into "keep", "toss" and "donate". These efforts raise important questions, specifically, who is the authority that decides what we keep, toss or donate? Thus, Tickle says, the cultural rummage sale always come back to a crisis of authority.

The rise of the Protestant Reformation saw the Papal authority called into question and the authority of the Bible was elevated. This year marks 500 years since Luther's ninety-five thesis nailed on a door, and the crisis of authority is upon us.

I have noted the difference in sola scriptura and prima scriptura and how United Methodists have a stronger history and connection to prima scriptura than sola. By way of a metaphor I would like to offer up that for the UMC, scripture is the Christian DNA.

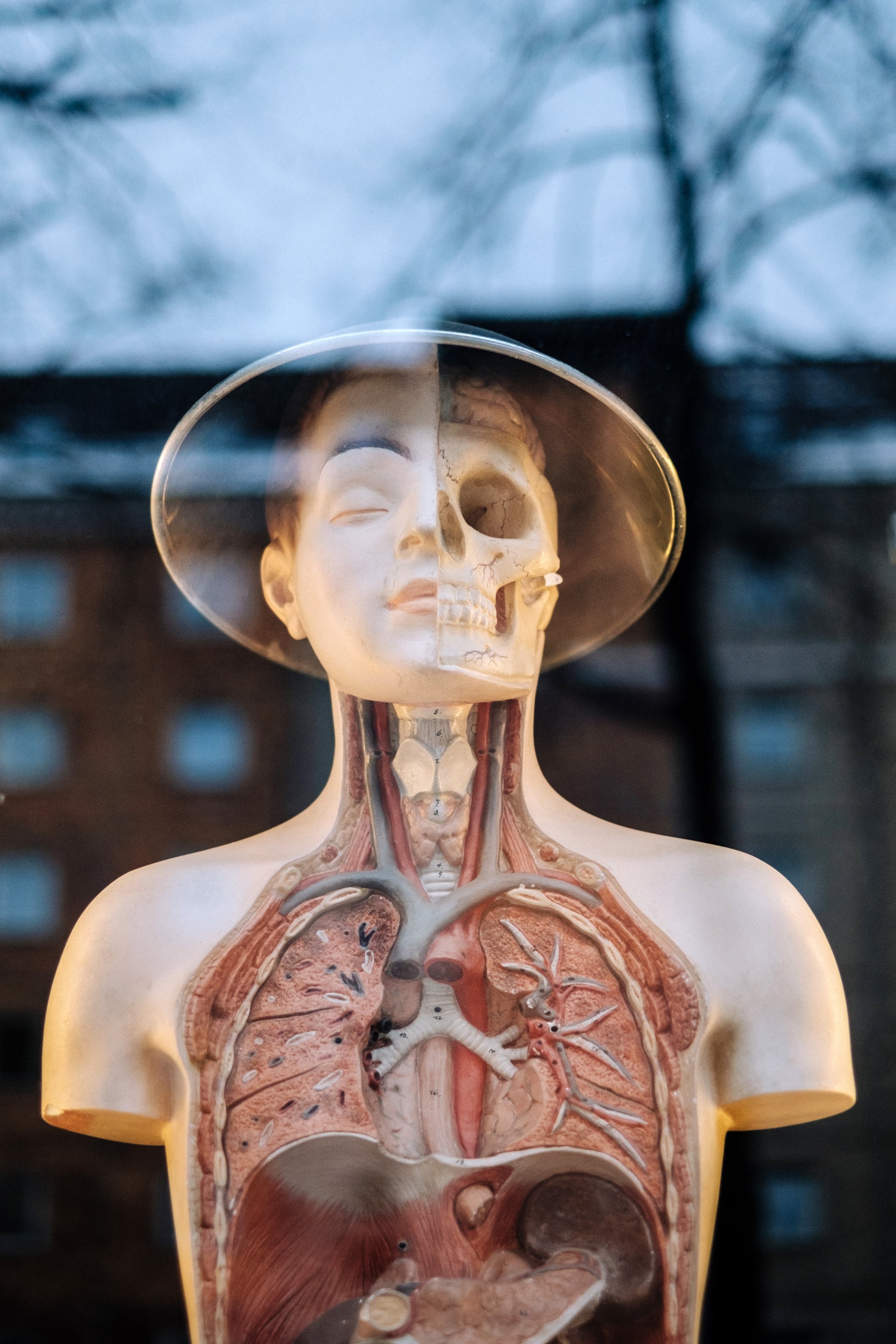

The debate between nature (DNA) and nurture (environment) is setting when it comes to human beings. What makes a human being is not nature OR nurture, but nature AND nurture. DNA is our first draft and our environment can influence our bodies but our DNA is our starting point. Likewise, scripture is our starting point, but we understand the environment effects the writer and reader of that very scripture. Scripture is the Christian DNA - it is our first draft it is where we start.

Humans once had a need for tailbones and wisdom teeth, and the environment has made those parts of us no longer as critical. There are things in scripture that were at one time very helpful to culture, but culture has evolved and those same scripture are less critical.

I do not fear the environment of tradition, experience and reason having an effect on the Christian DNA. Rather I celebrate that Christianity is a religion that is alive and that the scripture is called "the living word". I celebrate that our scriptural DNA is robust to respond to the ever changing situations facing the world while. I celebrate that scripture is robust enough to exist in a variety of environments and give everyone an excellent starting point to engage in a relationship with God in Christ through the Holy Spirit.

We Are All Afraid in the #UMC. Great. Can We Move On Yet?

Everywhere I look and read there is some element of fear that is being described. For instance in the conversation around the inclusion of LGBT Christians in the UMC, each side claims the other side is fearful. One side says that the other is fearful of change. Another side says the other is fearful of being out of step with culture. One side says the other is fearful of a slippery slope. Another side says the the other is fearful of embracing the full authority of scripture. Everyone says the other side is afraid.

In some circles you may hear that everyone is afraid and even go a step farther in sharing what they are afraid of. Owning what we are each afraid of is cathartic, but it does not seem to produce much fruit. In fact, talking about fear seems to only amplify the fear that may not even be out there!

Instead of talking about our fears, can we just take at the starting point that we all are afraid? Can we move the conversation around LGBT inclusion from "what are you afraid" of to something like "what do you value"?

My son is four years old and he says he is afraid of the dark. However, in addition to being afraid of the dark he is also fearful of deep water and caves. At night I can give him a flashlight. I can ensure he stays in the shallow end and in the suburbs it is not difficult to avoid caves. The "thing behind the thing" around my son's fear of the dark, deep water or rocky crevasses is that he values being able to see clearly. Now if you listen to my son talk about what he is afraid of you will miss the underlying value that informs (drives) his behavior.

Likewise in the Church. When we spend time listening to the fears of another person, this is a pastoral action and it is important. However, if we are only listening to fears we can miss the underlying value that drives those fears.

The final point I want to elevate when talking about fears is that it is easy to dismiss the other person as not having legitimate fears. When we hear the fears of others and then speak to our own fears we often discount our partners fears as being less important as our fears. Playing the game of who has the most legitimate fear is a relational earthquake that shakes foundations, rupture relationship and crumbles bridges.

Rather than talking about fears, can we talk about values? Can progressives and traditionalists see that our values are aligned? Talking about values shifts the conversation from what arrests our actions to what can we do to live out these shared values?

We Are All Afraid. Okay. Can We Move On Yet?

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.